Fitness

Part I: Working out what it means to me

This article is an attempt to outline my motivation to exercise and the framework I use to incorporate fitness and health-related information/advice. I hope that ideas presented here provide the reader with some structure and an excuse to re-evaluate their own approach to this topic.

I’ve always wanted to be “strong” for reasons that have evolved with age. These have ranged from the sociological (performance in sport, body aesthetics), to the practical (opening pickle jars, staying injury- and disease-free), to the philosophical (elevated consciousness).

As I entered my 30s, I experienced changes in my own body first-hand (slower to recover, more stiff) and suffered a spate of injuries. As stiffness, pains, and aches started becoming more noticeable, I wondered if I could make changes to my lifestyle to prevent injuries and improve baseline health.

It turns out that finding reliable advice for such a common human experience is hard! I don’t want to become a professional athlete and I’m not a 15-year old with a highly flexible metabolism and capacity for quick recovery. The disconnect between advice to eat vegetables + walk a bit vs. curate micronutrient profiles + workout over 20 hours/week is vast. How should I pick the next thing to incorporate in my life?

First steps towards goal-setting

It helps to be a bit more clear about the desired outcomes that will inform my choice of actions:

Healthy aging and quality of life

It is well established, but surprisingly not as well known that we consistently lose muscle mass as we age beyond ~25 years of life. The loss is due to both a reduction in the number of muscle cells as well as atrophy of individual cells. Neuronal control of muscles degrades, and flexibility of joints declines as well (see Mitchell et al. 2012 for a review of aging in this context). The pathological version of such losses in muscle mass (strength) are referred to as sarcopenia (dynapenia) respectively, see Larsson et al. 2018 for an overview.

Similarly metabolic syndrome is a growing global epidemic, with low physical activity and poor diet being identified as drivers of a broad range of health issues. A couple of excerpts from a review by Saklayen M., 2018:

Metabolic syndrome, variously known also as syndrome X, insulin resistance, etc., is defined by WHO as a pathologic condition characterized by abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

The two basic forces spreading this malady are the increase in consumption of high calorie-low fiber fast food and the decrease in physical activity due to mechanized transportations and sedentary form of leisure time activities. The syndrome feeds into the spread of the diseases like type 2 diabetes, coronary diseases, stroke, and other disabilities.

The current consensus is that while some degree of aging-related physical decline is inevitable, we can preserve our abilities and slow down losses with consistent and targeted physical activity and diet changes.

Heightened access and awareness

The second outcome I desire is harder to quantify and therefore more subjective. Sensing the external and internal universe as keenly as possible is a joy to me. Improving my ability to access feedback from the body not only enables better control for voluntary movements, but also serves as a guide for how actions and lifestyle choices impact the body internally.

Concepts of voluntary control, attention, proprioception, as well as the notion of consciousness are all related and not quite separable. It is not controversial to claim that these are all influenced positively through a practice of deliberate breathing, focused thought, and controlled movement irrespective of the label assigned to the practice (e.g. yoga, pranayam, tai chi, qigong, box breathing etc).

Using healthcare systems well

In picking up injuries and interacting with the healthcare system over the last few years, I realized that knowledge of the body can inform steps for early action towards prevention and staying out of the healthcare system altogether.

Moreover, knowledge empowers the patient to problem-solve along with the professional by seeking out appropriate level of care, and by following up effectively once a course of action for recovery has been decided upon. An inability to understand and evaluate our own body contributes to a mistrust in the process, delays in recovery, additional expenses, and an avoidable burden on the healthcare system (see this recent JAMA commentary about the high cost of unnecessary care, borne by individuals and society at large).

Why is this hard?

Adapting cultural knowledge is difficult

Traditions and cultural knowledge might serve as robust, time tested way of incorporating certain habits (as some put it, habits that are Lindy). However our diet, lifestyle, and environment seem to be changing too rapidly to permit a straightforward match with practices of the past (these NatGeo essays are fascinating reads about the evolution of diet, and about shifting of diets as a key requirement to meet the challenge of feeding 9 billion people in the near future).

In my own experience, sources for knowledge of cultural practices are inaccessible or muddy. Inter-generational transmission of knowledge is no longer insulated from the influence of social media, and social media sources are rife with misinformation and motivated reasoning in the service of consumerism. Individuals with the ability to convince so often lack the competence to advise, yet have a dangerously large reach on online platforms. If our heuristic for cultural knowledge is “I’ve heard it many times” without a recognizable source or framework to refer to, the chances of being misled are high.

It is the same with accessing knowledge from ancient texts. Without a serious, systematic inquiry conducted by independent experts to understand the context, content, expressed degree of confidence etc. information within such texts can neither be accessed first hand, nor validated or adapted with the best tools we have access to today. Without a critical view, we remain susceptible to claims of universal cures made by self-styled gurus and influencers.

Systemic incentives are misaligned

Run a marathon. Participate in a sports league. Drink a beer while running1. Showcase grit in the mud2. Such activities are peddled to adults everywhere these days, driven by capitalist objectives and incentivized by the promise of social interaction.

Push through the pain. Mind over matter. Treat yourself to ice cream and alcohol after. The extent to which participants are encouraged to become numb to physical feedback, and indulge in harmful bingeing as reward in lieu of physical effort is bizarre. Participants are bombarded with cues to suggest that the supplements, energy drinks, and gear they don’t yet possess are holding back their performance. The incentives designed to promote a healthy life, and those to promote consumerism diverge fast.

Moreover, performance and long-term health are distinct goals. Performance requires foundational fitness, without which the excitement and competitive spirit encouraged in social sporting events makes it easy to push an ill-prepared, fatigued body into compromised positions. Tales of suffering and injuries picked up by middle-aged participants in the pursuit of completing races and sports competitions are not uncommon.

The way forward

We mostly have access to top down actions, which relate to movements we practice, diets we adhere to, and environments we structure for ourselves. The challenge is in evaluating how these actions affect us, and whether they help us progress towards our broad goals.

Top down evaluation

We might consider external, task-specific measurements (e.g. time to run 100m, maximum weight one can deadlift), body characteristics (e.g. joint range of motion, body weight and composition, heart rate, nominally invasive measurements such as glucose response, lactate response) and subjective feedback (e.g. tracking fraction of time body feels alert or lethargic over course of a day).

These different measures are not necessarily correlated with one another, and over-indexing on one measure can end up distracting from the goal of overall health. For example, one might be able to lift very heavy weights, but still have sub-par range of motion even in related limbs and joints; a persons’ body weight could be in normal ranges, but proportion of adipose tissue to muscle mass may not be etc.

Moreover, our body is a very complex biological system, and we are nowhere close to being able to determine an individuals health status completely with any set of finite measurements. Recognizing this complexity can help us avoid pitfalls.

In particular, Goodhart’s law warns that a measure treated as a target can (inadvertently) create perverse incentives. Related to that, Campbell’s law cautions against the over-reliance on quantitative proxies for decision-making in complex systems. Emphasizing improvement along narrow measures can mislead us, away from the true objective (which may not be captured fully through quantitative measurements)3.

Nevertheless, clinical settings can and do benefit from heuristically defined quantifiable assessments e.g. short physical performance battery, see footnote 4 for a short description.

We might similarly do well to cycle through a broad set of metrics, focusing on a manageable handful at any given time. While this top-down approach to evaluating actions seems tangible, it lacks grounding in terms of a clear understanding of what it means to be fit5.

Integrating basic science

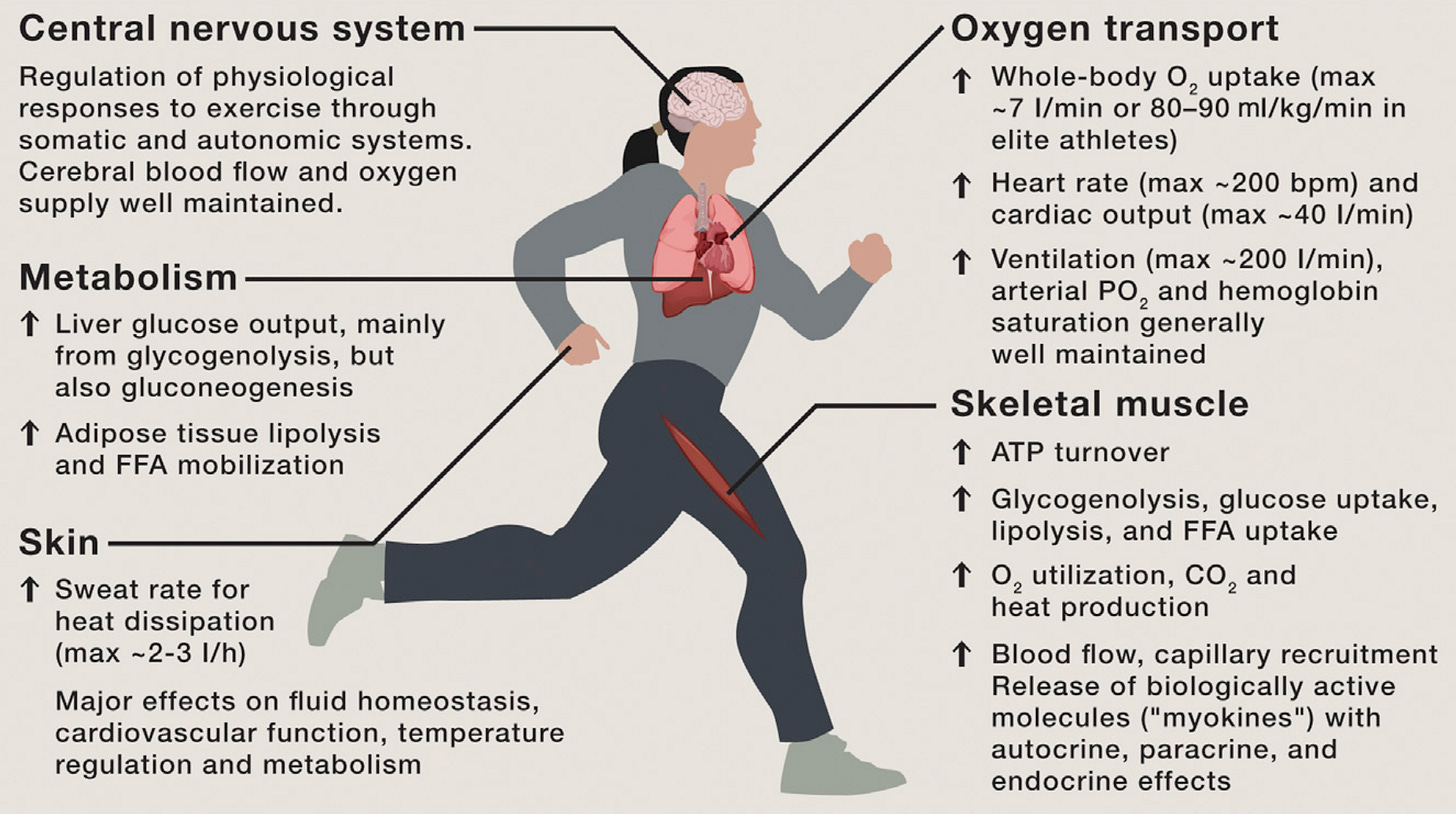

Changes in the body are ultimately a manifestation of changes accumulated at the cellular and sub-cellular levels. Understanding how actions influence normal function, adaptation in terms of molecules, cells, and organ systems involved in homeostatic mechanisms and metabolic pathways that regulate and maintain the body is the focus of a bottom-up approach to evaluating actions. “Integrative biology of exercise” by Hawley et al. 2014 is a great first read for anyone wanting go down this road.

Incidentally, new tools to study key life defining molecules (DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids etc.) with resolution and context not possible just a decade ago are now being adopted by scientists at a frenetic pace (e.g. see mission of the Human Cell Atlas project). With it, we continue to unravel a dizzying complexity that makes our bodies work.

Relating such top-down and bottom-up approaches to understand exercise is a major focus of recent research funded by the National Institutes of Health (see Neufer et al. 2015, Sanford et al. 2020, in relation to the MoTrPac consortium) and elsewhere, e.g. Stokes et al. 2020.

Insights from such research are fueling new commercial sensors and assays aimed at helping the general public to improve and monitor health, as opposed to diagnosing and monitoring disease (e.g. continuous glucose monitors, lactate measurement kits; also see Robbins et al. 2016 and related press coverage). Such sensors and assays can enable the translation of knowledge acquired through the bottoms up approach into tangible evaluation of actions.

Epilogue

I started writing this post in early 2022, with a naïve intention to summarize everything I learnt about strength and fitness in one easy-to-digest article. As my understanding grew, so did the number threads I started pursuing. This article is now a first of many I plan to write around themes of health and fitness.

I don’t have any universal advice at this point, only some context, a framework, and a set of recent, well-cited scientific literature that could serve as entry points for your own exploration. The lesson I’ve learnt this far is that continued education and a willingness to update habits can help us avoid known pitfalls and lead healthier lives.

Updates

Dec. 2023: Part II is an update on where I’m at a year after I wrote this post.

“Chug run chug” by journalist-writer Molly McHugh offers a window into the bizarre phenomenon of beer runs.

Maybe tolerating explosive diarrhea is an indicator of how tough one is. Maybe.

Goodhart’s law and its variants (see this blog post and preprint) crop up in various contexts, most recently in discussions around alignment of AI.

The short physical performance battery (Guralnik et al. 1994) incudes assessments based on walking speed, chair stand, and balance time. It has been widely used to assess lower extremity function, and is an attempt to capture health status in older populations in clinical settings - see Pavasini et al. 2016 for an overview.

Biomechanics, i.e. positioning the body to generate and transmit forces safely and effectively while respecting constraints placed by the individual’s anatomy, is a principled way to evaluate movement patterns - although integrating it with cells and molecules remains a challenge.